From Paris to London: How Nour Abida Found Belonging Through Food, Film and Creativity

Nour is a delight. Truly. She’s a ray of sunshine: and honestly the only person I’d be patient enough to listen to about Taylor Swift. Calm, quiet, powerful. Observant and insightful. That’s exactly why I had to interview her.

With a father from Tunisia and a mother from Martinique, Nour grew up in a rich, layered world. Her parents came to Paris to build something beautiful, and at 17 she left Paris for London on her own. Many of us who are children of migrants find ourselves in a strange place now. Our parents were brave enough to uproot themselves for a new life - many not by choice- in a country nothing like their own, and here we are: many of us curious and tired of the environment we were raised in. Maybe it’s time we channelled that same bravery like Nour’s parents. Explore new cities. Move if you need to, if you can. Everywhere is a bit shit, but honestly… do it if you can.

Reading Nour’s interview, my biggest takeaway - for myself and for you - is simple: take photos. Document everything.

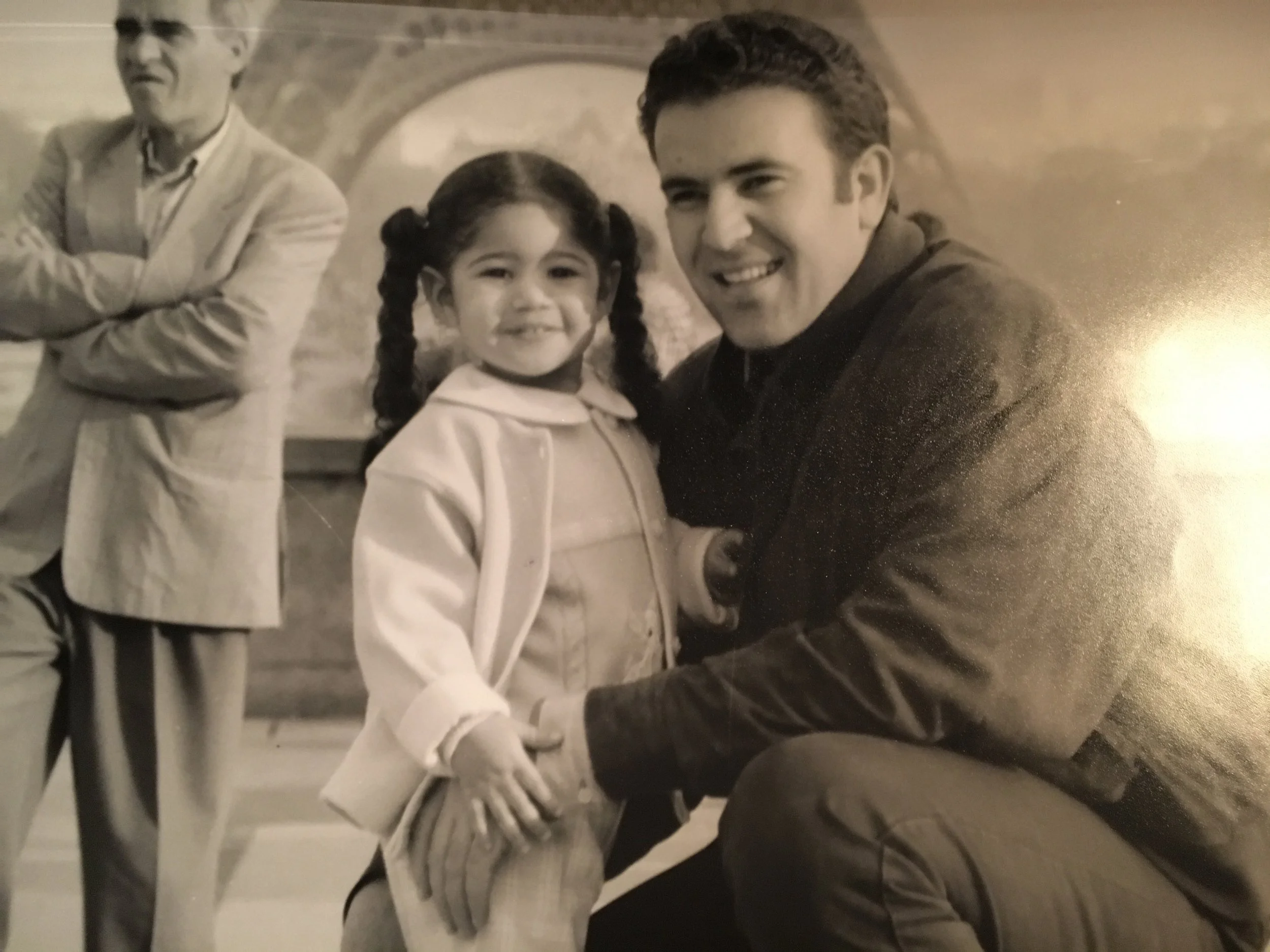

Looking through Nour’s own photos, from being two years old with her dad at the Eiffel Tower to her first day at Coventry University on her journalism course, you realise how powerful it is to capture your life. Photos show you your growth, your distance, your becoming. They’re the aroma of the lives we’ve lived. They remind us who we were, who we loved, how far we’ve come: and how far we’ve still got to go.

And taking photos doesn’t have to mean posting them online. Take them. Keep them. Let them be yours.

“I was lucky to grow up in a mixed household. Cooking was also its own form of communication in my family to show love. On the Tunisian side, there wasn’t always an explicit apology after a disagreement, but someone would quietly prepare something special, and that was how we reconciled.”

Nour speaking about her debut documentary ‘The Homecoming’ (Photo credit: Kenny Tran)

Nour’s Food Profile

Your go-to comfort food? Tunisian Mloukhia, briques or Laksa.

If you could be a fruit or vegetable, what would it be, and why? Mangoes (specifically from grandma’s tree in Martinique)

Food item that reminds you of your childhood? Mloukhia, briques, crab colombo or scoubidous threads (sweets)

Current favourite restaurant? Middle Eastern Food in Marwa Food Court, Hounslow

Nour eating a mango from her grandmother’s tree in Martinique.

The Interview

You were born to a Tunisian father and a French mother from Martinique. What did food look like for you in your childhood?

I was very lucky to grow up in a mixed household in the city of Ormesson where we always had flavourful food. Cooking was also its own form of communication in my family: to show love, but not just that. On the Tunisian side, there wasn’t always an explicit apology after a disagreement, but someone would quietly prepare something special, and that was how we reconciled.

From my Martinican side, my grandmother’s Crabe colombo, a fragrant crab stew, and her Poulet boucané, the most perfectly smoked chicken, were the heart of every gathering.

Then there was my mum’s cooking, always with cream and love. My absolute favourite is Chicory baked with cream and cheese, but she also makes an aubergine-and-cheese bake that tastes like a hug, and a perfect gratin de pommes de terre that could turn any bad day around. She’s also a great baker and makes the best Crepes, gauffres, charlotte à la mangue, Tiramisu. From my Tunisian side, I was spoiled with Mlukhiya (a deep, earthy green stew that simmers for hours), comforting Chorba - a spiced Tunisian tajine (so different from the Moroccan one!), Moroccan tajine crispy Briques with a runny egg inside, and endless glibettes (sunflower seeds) to snack on. Couscous was a frequent ritual on Sunday.

Growing up in France, I didn’t eat much “classic” French food, until one day I tried raclette. I had always dismissed it as just cheese, potatoes, and charcuterie, but little did I know how wrong I was. The first bite was a revelation. And then there’s my lifelong love affair with French pâtisserie. French pastries are unparalleled: so delicate and subtle that every bite feels like a tiny celebration and walking into a pâtisserie still feels like I’m stepping into an art gallery. Looking back, I realise I was raised not just on flavour, but on generosity. Food was always shared, always plentiful, always a way to gather everyone back around the table.

Why did you decide to leave Paris?

At 17, I felt like I was standing at the edge of my life with no idea where to step next. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, and felt like I had no further prospects in life, so I decided to spend a year in England to learn English. That “one year” turned into a new life, I never went back to France. In some ways, I was continuing a family tradition: my dad left Tunisia for France, and my mum left Martinique to study there. Leaving to seek a bigger horizons is in my DNA. What I didn’t expect was that my choice would inspire my brother and sister to follow me to England too.

Nour’s best friends seeing her off at the Eurostar as she left for London at 17

What was the biggest cultural shock you experienced moving to London?

There were so many! One of my earliest shocks was going to a UK supermarket, buying an éclair, and realising it was filled with whipped cream. In France, éclairs are filled with light and delicate pastry cream, and each eclair flavour has its own filling , so I stood there in disbelief. I know it sounds terribly posh, but I still remember the disappointment even though now I’m used to it and it has become my guilty pleasure.

Then there was the learning style which took some adjusting. In France, education is very formal, calling your professor “Monsieur” or “Madame" followed by their surname is the norm. So the first time I heard people call lecturers by their first name, I thought, “This is insane, where is the respect?”

Next is the communication style. In France, people are sparing with praise, no one calls you “brilliant” unless you’re basically Einstein. The first time someone told me my idea was “brilliant,” I was ready to frame the compliment!

Eating habits are different too. In France, meals are long, almost ritualistic. You linger at the table, you talk, you debate. In the UK, I noticed that sometimes, things tend to be faster. And yet, I felt less judged here, especially in how I dressed. London felt freeing, like I could experiment and nobody would care.

Now the hardest part? The hugging. In France, we kiss on the cheek, which somehow at the time felt less intimate. Hugging a near-stranger felt incredibly personal, but now I’m used to it I think I prefer it to cheek kisses.

What advice would you give to someone leaving home to start over elsewhere?

Be patient with yourself. It takes time for a place to become home. From a practical perspective, save what you can, but also invest in connection.

What worked for me: I joined my local choir, got to know my neighbours, and I volunteer for my local community. These small acts create the threads that weave a safety net around you. I know that society today praises individualism but I really felt that community spirit.

And remember to celebrate your wins, even the small ones and document them. I love taking photos so I can look back and remember all the little moments that built my new life. Sometimes I journal too, because writing helps me see how far I’ve come.

Growth often happens outside your comfort zone, so don’t be afraid to try new things, even if they scare you. And if you feel like you’re running out of time, remind yourself that you’re not. Life isn’t a race.

For me, creativity has been my compass. Painting, writing, making things: anything that keeps me connected to joy has helped me through the hardest seasons. And I often stop to ask myself: Who am I? What makes me truly happy? Those questions are as important as any map when you’re building a new life.

(From L-R: Nour’s first journalism internship in Martinique & Nour filming her debut documentary ‘in 2023, The Homecoming’

You’ve mostly worked behind the scenes as a journalist, but you stepped in front of the camera for your debut documentary, The Homecoming. What was that like?

I had presented a weekly business TV programme before, but a feature-length documentary for the BBC was a completely different experience. This time, I wasn’t just reporting, I was stepping inside the story.

I was surrounded by the most incredible team, and that made all the difference. The producer, Nathalie Jimenez, was instrumental in shaping the narrative and guiding me through the process with such care. The team supported me at every step. It never felt like I was doing this alone, and that gave me the courage to be vulnerable on screen.

But the heart of the film was our contributors. They were so generous with their time and their trust, opening their homes to us, sharing deeply personal journeys with honesty, and reminding me why I became a journalist in the first place.

There were moments that felt surreal , like sitting down for raclette with one family, or sharing thieboudienne (Senegalese jollof rice and fish) while listening to their stories. I remember thinking, ‘Wow. This is my job?’

Yes, making a film like this can be emotionally demanding, but it comes with so much privilege. To be trusted with people’s stories, to witness their lives up close, and to have a team that holds you up through the process, that’s something I will never take for granted.

The impact was extraordinary, especially the discussion that it sparked globally. The film has been viewed by over four million people across online platforms, making it one of BBC Afrique’s top-performing documentaries of 2024. Screenings sold out in Paris (in 10 minutes), London, Dakar, and New York. At these events, diaspora audiences debated openly with academics, policymakers, and the organisation’s leaders. A woman attending said: “This film allowed me to express feelings I had buried for 30 years.” Another young man said: “For the first time, I saw my history, my legacy, told by people like me. This is a documentary I’ll show my children.”

Nour in 'her debut documentary, ‘The Homecoming’

What has been the most surprising part of your journey so far?

Honestly? Everything. I never imagined that the teenager who left Paris feeling lost would one day give a speech at the University of Oxford, be shortlisted for a fellowship there, see her work screened across the world, become a systems thinking practitioner, an artist, a French teacher, a mentor, and a mentee. All of this, whilst working as a journalist whose work would make her travel globally.

But perhaps the biggest surprise is realising how much creativity has been my anchor. Every time life felt heavy, experiencing burnout, heartbreak, loneliness - creativity was the one thing that saved me. Painting, writing, even dreaming up new projects have helped me turn pain into something beautiful.

And of course, the community I’ve built along the way is my proudest achievement. There was a time I felt completely alone. Now, I am surrounded by mentors, colleagues, and friends who cheer me on, every success feels like a collective celebration.

Over the years, I’ve grown so much, not just professionally but personally. Living abroad has taught me to look at things critically, to stop judging so quickly, and to see life with more nuance. It’s also deepened my appreciation for France, for the culture I come from, and for the choices my family made long before me. I understand now that every decision, leaving Tunisia, leaving Martinique, leaving Paris was about seeking a better future. That perspective has made me both softer and stronger.

How do you define success, and has that changed over time?

When I was younger, I thought success was about milestone: being on TV, making a documentary, getting a byline (your name on an article). Now, I see success as what happens afterwards: who gets lifted because of what you did, which doors you opened for others, what conversations you sparked.

Success, for me, is when impact is shared, when everyone has a seat at the table and equal opportunities, not just a privileged few. It’s knowing that the work I do creates space for others to thrive, not just for me to shine.

And it’s also deeply personal: success is being able to share what I have, time, resources, joy, with the people I love. It’s having enough space in my life to linger at the table with family and friends, to take holidays, to create freely, and to actually enjoy the life I’ve worked so hard to build.

When my work feels aligned with who I am and there’s room for both impact and joy, that’s when I know I’m successful.

Nour and her dad outside The Eiffel Tower