From Paris to London: How Nour Abida Found Belonging Through Food, Film and Creativity

Nour is a delight. Truly. She’s a ray of sunshine: and honestly the only person I’d be patient enough to listen to about Taylor Swift. Calm, quiet, powerful. Observant and insightful. That’s exactly why I had to interview her.

With a father from Tunisia and a mother from Martinique, Nour grew up in a rich, layered world. Her parents came to Paris to build something beautiful, and at 17 she left Paris for London on her own. Many of us who are children of migrants find ourselves in a strange place now. Our parents were brave enough to uproot themselves for a new life - many not by choice- in a country nothing like their own, and here we are: many of us curious and tired of the environment we were raised in. Maybe it’s time we channelled that same bravery like Nour’s parents. Explore new cities. Move if you need to, if you can. Everywhere is a bit shit, but honestly… do it if you can.

Reading Nour’s interview, my biggest takeaway - for myself and for you - is simple: take photos. Document everything.

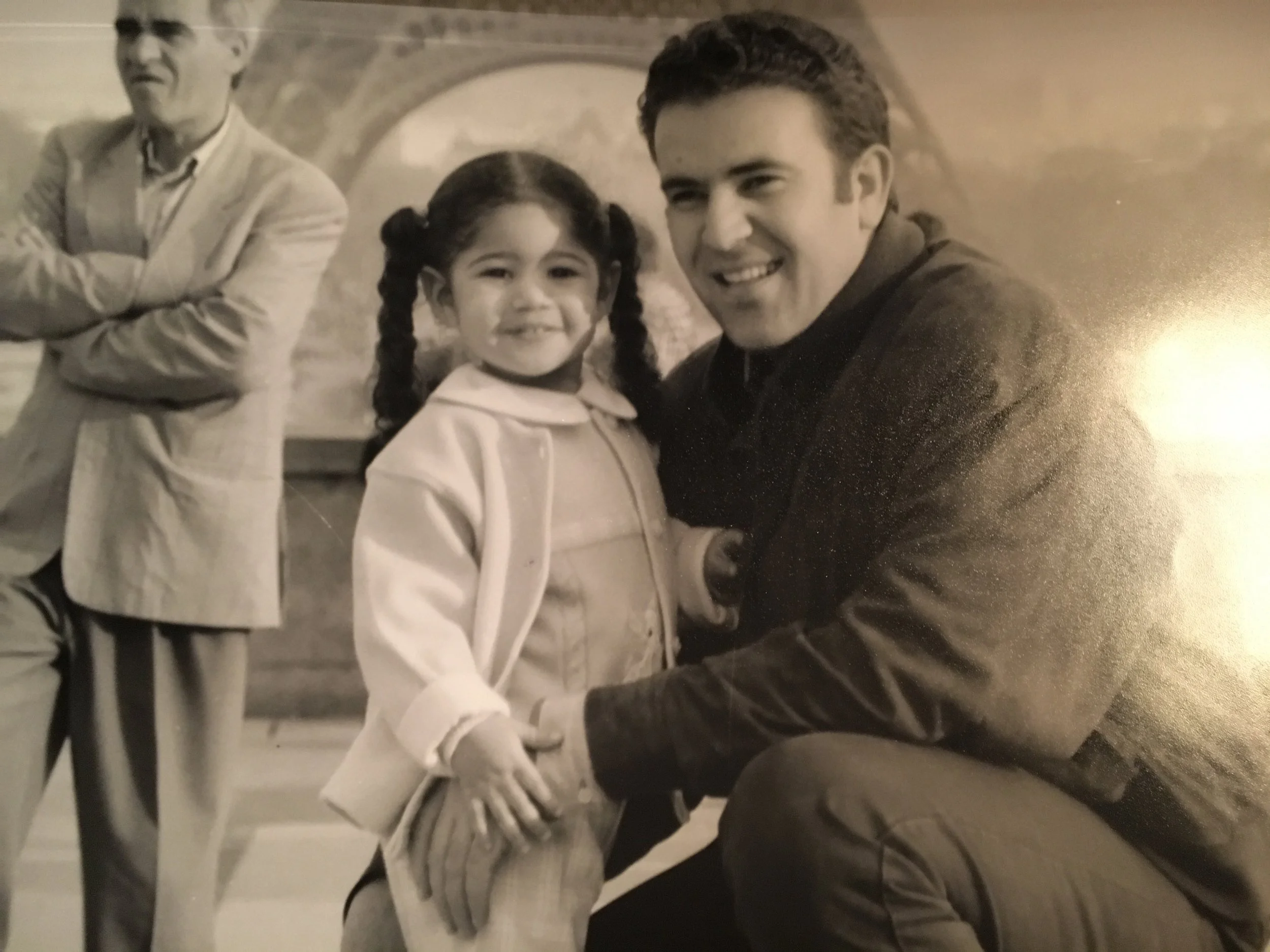

Looking through Nour’s own photos, from being two years old with her dad at the Eiffel Tower to her first day at Coventry University on her journalism course, you realise how powerful it is to capture your life. Photos show you your growth, your distance, your becoming. They’re the aroma of the lives we’ve lived. They remind us who we were, who we loved, how far we’ve come: and how far we’ve still got to go.

And taking photos doesn’t have to mean posting them online. Take them. Keep them. Let them be yours.

“I was lucky to grow up in a mixed household. Cooking was also its own form of communication in my family to show love. On the Tunisian side, there wasn’t always an explicit apology after a disagreement, but someone would quietly prepare something special, and that was how we reconciled.”

Nour speaking about her debut documentary ‘The Homecoming’ (Photo credit: Kenny Tran)

Nour’s Food Profile

Your go-to comfort food? Tunisian Mloukhia, briques or Laksa.

If you could be a fruit or vegetable, what would it be, and why? Mangoes (specifically from grandma’s tree in Martinique)

Food item that reminds you of your childhood? Mloukhia, briques, crab colombo or scoubidous threads (sweets)

Current favourite restaurant? Middle Eastern Food in Marwa Food Court, Hounslow

Nour eating a mango from her grandmother’s tree in Martinique.

The Interview

You were born to a Tunisian father and a French mother from Martinique. What did food look like for you in your childhood?

I was very lucky to grow up in a mixed household in the city of Ormesson where we always had flavourful food. Cooking was also its own form of communication in my family: to show love, but not just that. On the Tunisian side, there wasn’t always an explicit apology after a disagreement, but someone would quietly prepare something special, and that was how we reconciled.

From my Martinican side, my grandmother’s Crabe colombo, a fragrant crab stew, and her Poulet boucané, the most perfectly smoked chicken, were the heart of every gathering.

Then there was my mum’s cooking, always with cream and love. My absolute favourite is Chicory baked with cream and cheese, but she also makes an aubergine-and-cheese bake that tastes like a hug, and a perfect gratin de pommes de terre that could turn any bad day around. She’s also a great baker and makes the best Crepes, gauffres, charlotte à la mangue, Tiramisu. From my Tunisian side, I was spoiled with Mlukhiya (a deep, earthy green stew that simmers for hours), comforting Chorba - a spiced Tunisian tajine (so different from the Moroccan one!), Moroccan tajine crispy Briques with a runny egg inside, and endless glibettes (sunflower seeds) to snack on. Couscous was a frequent ritual on Sunday.

Growing up in France, I didn’t eat much “classic” French food, until one day I tried raclette. I had always dismissed it as just cheese, potatoes, and charcuterie, but little did I know how wrong I was. The first bite was a revelation. And then there’s my lifelong love affair with French pâtisserie. French pastries are unparalleled: so delicate and subtle that every bite feels like a tiny celebration and walking into a pâtisserie still feels like I’m stepping into an art gallery. Looking back, I realise I was raised not just on flavour, but on generosity. Food was always shared, always plentiful, always a way to gather everyone back around the table.

Why did you decide to leave Paris?

At 17, I felt like I was standing at the edge of my life with no idea where to step next. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, and felt like I had no further prospects in life, so I decided to spend a year in England to learn English. That “one year” turned into a new life, I never went back to France. In some ways, I was continuing a family tradition: my dad left Tunisia for France, and my mum left Martinique to study there. Leaving to seek a bigger horizons is in my DNA. What I didn’t expect was that my choice would inspire my brother and sister to follow me to England too.

Nour’s best friends seeing her off at the Eurostar as she left for London at 17

What was the biggest cultural shock you experienced moving to London?

There were so many! One of my earliest shocks was going to a UK supermarket, buying an éclair, and realising it was filled with whipped cream. In France, éclairs are filled with light and delicate pastry cream, and each eclair flavour has its own filling , so I stood there in disbelief. I know it sounds terribly posh, but I still remember the disappointment even though now I’m used to it and it has become my guilty pleasure.

Then there was the learning style which took some adjusting. In France, education is very formal, calling your professor “Monsieur” or “Madame" followed by their surname is the norm. So the first time I heard people call lecturers by their first name, I thought, “This is insane, where is the respect?”

Next is the communication style. In France, people are sparing with praise, no one calls you “brilliant” unless you’re basically Einstein. The first time someone told me my idea was “brilliant,” I was ready to frame the compliment!

Eating habits are different too. In France, meals are long, almost ritualistic. You linger at the table, you talk, you debate. In the UK, I noticed that sometimes, things tend to be faster. And yet, I felt less judged here, especially in how I dressed. London felt freeing, like I could experiment and nobody would care.

Now the hardest part? The hugging. In France, we kiss on the cheek, which somehow at the time felt less intimate. Hugging a near-stranger felt incredibly personal, but now I’m used to it I think I prefer it to cheek kisses.

What advice would you give to someone leaving home to start over elsewhere?

Be patient with yourself. It takes time for a place to become home. From a practical perspective, save what you can, but also invest in connection.

What worked for me: I joined my local choir, got to know my neighbours, and I volunteer for my local community. These small acts create the threads that weave a safety net around you. I know that society today praises individualism but I really felt that community spirit.

And remember to celebrate your wins, even the small ones and document them. I love taking photos so I can look back and remember all the little moments that built my new life. Sometimes I journal too, because writing helps me see how far I’ve come.

Growth often happens outside your comfort zone, so don’t be afraid to try new things, even if they scare you. And if you feel like you’re running out of time, remind yourself that you’re not. Life isn’t a race.

For me, creativity has been my compass. Painting, writing, making things: anything that keeps me connected to joy has helped me through the hardest seasons. And I often stop to ask myself: Who am I? What makes me truly happy? Those questions are as important as any map when you’re building a new life.

(From L-R: Nour’s first journalism internship in Martinique & Nour filming her debut documentary ‘in 2023, The Homecoming’

You’ve mostly worked behind the scenes as a journalist, but you stepped in front of the camera for your debut documentary, The Homecoming. What was that like?

I had presented a weekly business TV programme before, but a feature-length documentary for the BBC was a completely different experience. This time, I wasn’t just reporting, I was stepping inside the story.

I was surrounded by the most incredible team, and that made all the difference. The producer, Nathalie Jimenez, was instrumental in shaping the narrative and guiding me through the process with such care. The team supported me at every step. It never felt like I was doing this alone, and that gave me the courage to be vulnerable on screen.

But the heart of the film was our contributors. They were so generous with their time and their trust, opening their homes to us, sharing deeply personal journeys with honesty, and reminding me why I became a journalist in the first place.

There were moments that felt surreal , like sitting down for raclette with one family, or sharing thieboudienne (Senegalese jollof rice and fish) while listening to their stories. I remember thinking, ‘Wow. This is my job?’

Yes, making a film like this can be emotionally demanding, but it comes with so much privilege. To be trusted with people’s stories, to witness their lives up close, and to have a team that holds you up through the process, that’s something I will never take for granted.

The impact was extraordinary, especially the discussion that it sparked globally. The film has been viewed by over four million people across online platforms, making it one of BBC Afrique’s top-performing documentaries of 2024. Screenings sold out in Paris (in 10 minutes), London, Dakar, and New York. At these events, diaspora audiences debated openly with academics, policymakers, and the organisation’s leaders. A woman attending said: “This film allowed me to express feelings I had buried for 30 years.” Another young man said: “For the first time, I saw my history, my legacy, told by people like me. This is a documentary I’ll show my children.”

Nour in 'her debut documentary, ‘The Homecoming’

What has been the most surprising part of your journey so far?

Honestly? Everything. I never imagined that the teenager who left Paris feeling lost would one day give a speech at the University of Oxford, be shortlisted for a fellowship there, see her work screened across the world, become a systems thinking practitioner, an artist, a French teacher, a mentor, and a mentee. All of this, whilst working as a journalist whose work would make her travel globally.

But perhaps the biggest surprise is realising how much creativity has been my anchor. Every time life felt heavy, experiencing burnout, heartbreak, loneliness - creativity was the one thing that saved me. Painting, writing, even dreaming up new projects have helped me turn pain into something beautiful.

And of course, the community I’ve built along the way is my proudest achievement. There was a time I felt completely alone. Now, I am surrounded by mentors, colleagues, and friends who cheer me on, every success feels like a collective celebration.

Over the years, I’ve grown so much, not just professionally but personally. Living abroad has taught me to look at things critically, to stop judging so quickly, and to see life with more nuance. It’s also deepened my appreciation for France, for the culture I come from, and for the choices my family made long before me. I understand now that every decision, leaving Tunisia, leaving Martinique, leaving Paris was about seeking a better future. That perspective has made me both softer and stronger.

How do you define success, and has that changed over time?

When I was younger, I thought success was about milestone: being on TV, making a documentary, getting a byline (your name on an article). Now, I see success as what happens afterwards: who gets lifted because of what you did, which doors you opened for others, what conversations you sparked.

Success, for me, is when impact is shared, when everyone has a seat at the table and equal opportunities, not just a privileged few. It’s knowing that the work I do creates space for others to thrive, not just for me to shine.

And it’s also deeply personal: success is being able to share what I have, time, resources, joy, with the people I love. It’s having enough space in my life to linger at the table with family and friends, to take holidays, to create freely, and to actually enjoy the life I’ve worked so hard to build.

When my work feels aligned with who I am and there’s room for both impact and joy, that’s when I know I’m successful.

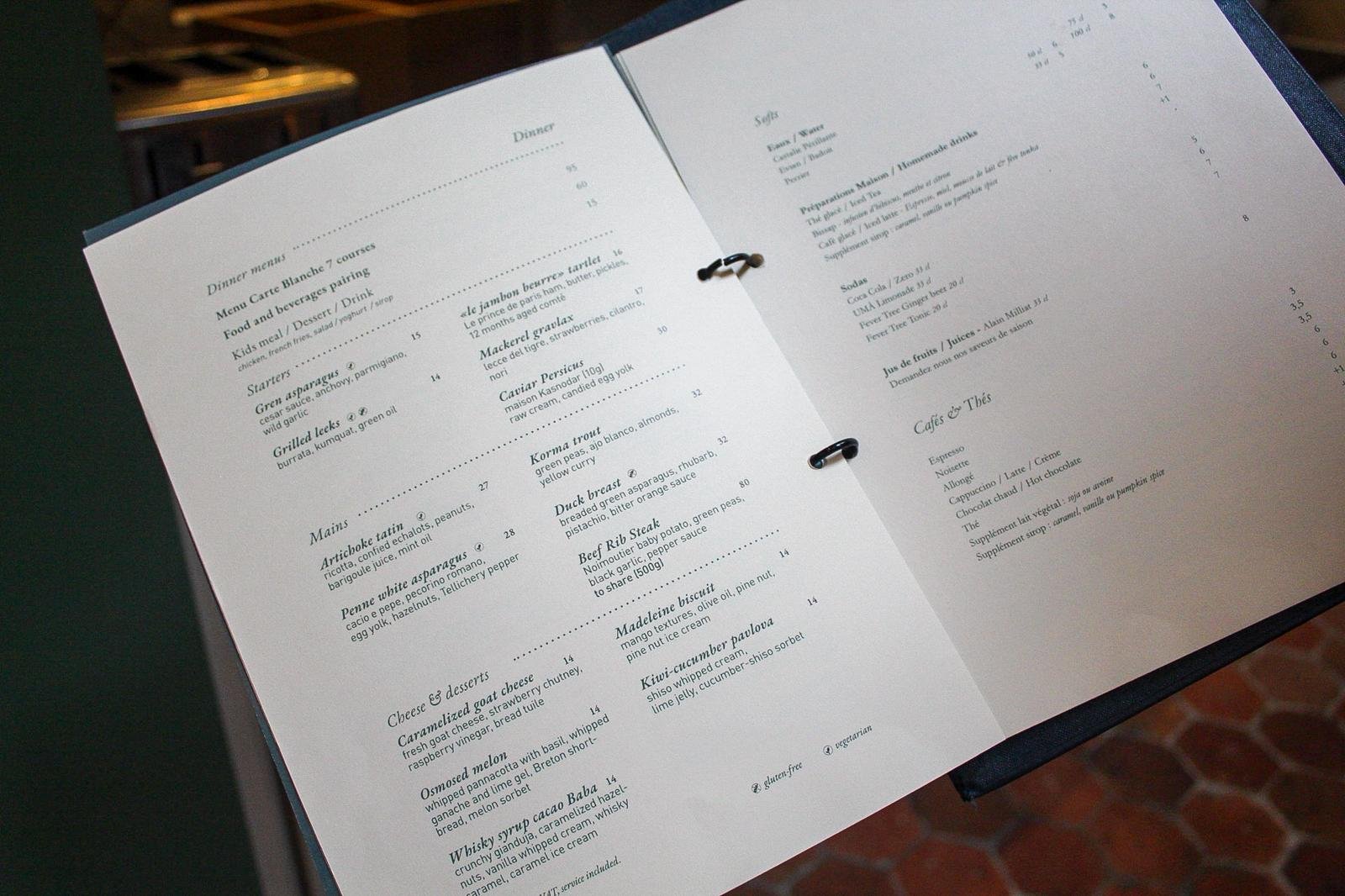

Nour and her dad outside The Eiffel Tower

Meet Ashwin

Raised in France and of Indian descent, Ashwin has one of the most fascinating cultural backgrounds I’ve come across in a while. He grew up in Paris but spent many childhood summers in Pondicherry (or Puducherry), a beautiful coastal town and former French colony in India. His grandfather was raised in Vietnam, while his grandmother spent her formative years first in Pondicherry and later in La Réunion, a small island dotted in the Indian Ocean.

While we spoke at Arbore, the French-Indian restaurant where Ashwin serves as executive chef (he also developed the menu), it became clear how much his diverse cultural heritage, childhood memories and travels shape not only his food, but his approach to life.

What makes Ashwin’s journey unconventional is the depth of exploration into his heritage. His openness and respect for the unfamiliar are reflected in his cooking, his life philosophy and his very definition of success.

I’ve been lucky to grow up in a city as diverse as London, yet through Ashwin I was reminded that even within cultures we believe we know well, there is always more to discover.

“On the very first day of culinary school, I went home that night and told my parents, ‘This is the best day of my life.’ I was finally doing something I loved.”

Ashwin Marius Le Prince

Ashwin’s Food Profile

Go-to comfort food? Carbonara

If you could be a fruit or vegetable, what would it be and why? A Mango. I grew up around lots of them!

What’s a food item that reminds you of your childhood? My Grandma’s Coconut Broth served with rice & meat

Restaurant you’re currently loving? Il Brigante (Paris, 18e). An Italian pizzeria

Restaurant you want to visit next? Vaisseau by Top Chef’s Adrien Cachot (Paris, 11e)

The Interview

Tell me about your childhood?

After getting my Baccalaureate at 18, I went to a culinary school in Paris called CFA Médéric. Culinary school lasted three years, and each year included a paid placement in a different restaurant. The first year I learnt key culinary skills, and the next two were more about management and accountability.

Life in Paris was great. From 18, I was always outside meeting people and exploring the city. I think my curiosity helped me put myself out there, and the time I spent in Pondicherry really helped build my confidence. My grandfather would take me to the market daily and he spoke to everyone! I think I picked that up from him. It’s why I make a point to greet my neighbours, know their names and build that same kind of community around me today.

You spent quite a lot of time in India. What are your fondest memories of Pondicherry?

I grew up in Paris but visited Pondicherry with my family every two years from birth. After finishing my studies, I returned at 22 to live in Pondicherry and work there as a chef for a year. When I used to visit with my parents, I didn’t get to experience much of everyday life. I didn’t go out on my own, you would stay in the family home or go to the same restaurants. But living there on my own was completely different, it was amazing. I worked with locals, teaching them culinary skills whilst they taught me more about Goan cuisine. But more than the food, I learned from their humility, sense of community and generosity. They had little, but they shared a lot. That sense of community changed my perspective. It made me more grateful for what I had and reminded me to find happiness in my own life.

Ashwin with his grandparents in Pondicherry

What’s a dish that reminds you of your childhood?

My grandma’s coconut broth. She would start by frying mustard seeds and curry leaves in coconut oil, then add coconut milk, turmeric and tamarind. We would eat it with rice and some fried meat. Also, most mornings, I would wake up to French toast. Then my grandfather would take me to the market, and when we came back, my grandma would cook with whatever we bought.

Was becoming a chef something you dreamed of?

Yes, but whilst I was in school and even into my first year of culinary school, being a chef wasn’t seen as glamorous. It was seen as something you did if you had no other career options. There were no big culinary TV shows like Top Chef back then. I was lucky that my parents supported me. They didn’t push me to be a doctor or lawyer, they just said I had to finish my general studies until I was 18, so I had a solid foundation. After that, I could pursue what I wanted.

Ashwin’s coconut dish, inspired on his grandmother’s coconut broth.

When did you realise cooking could be more than a passion?

I knew from the age of 10 that I wanted to be a chef and own a restaurant one day. But I had to complete my general studies even though I didn’t want to be there. So once I turned 18, I went straight to culinary school. On the very first day, we learnt how to cut fruit and vegetables. I remember going home that night and telling my parents, “This is the best day of my life.” I was finally doing something I loved.

You have such a unique multi-cultural background and history. How did this shape your identity as a chef?

I am the Executive Chef at Arbore, where I developed the menu. It has an Indian-French influence, but also includes Vietnamese flavours which was influenced by my grandfather who was raised there. I’m also inspired by Creole flavours thanks to my grandmother who was raised in La Réunion.

When it comes to developing a new menu, I do not force the creative process. When I create a fusion dish with Indian influence, it’s often tied to a memory from childhood, like something my grandmother made.

What advice would you give to aspiring chefs?

You can’t escape phases: don’t be in a hurry. Learn, because mastery takes time and challenges will help you become a better chef. For example, 10 years ago, if I had the money to open a restaurant, it wouldn’t have lasted because I didn’t have the experience of running one. Now I can run a restaurant successfully because I’ve had the time to learn the business side. I meet a lot of young chefs who want to make complicated dishes overnight because they see me do it easily. But I tell them, if it looks easy it’s because I’ve practised for years. It’s like the Picasso story, when someone asked him why a sketch cost so much when it only took him a few minutes to complete it, and he replied, “No, it has taken me 40 years to do it that quickly.”

Ashwin Marius Le Prince (Credit: food2vous)

There are many chef shows like The Bear. How accurate are these shows of the kitchen? (Sadly Ashwin does not watch ‘Emily in Paris’!)

I’ve watched Season 1 of The Bear, I think it’s quite accurate on what happens in the kitchen. The stress, the decisions, the personalities. The angry chef, the pressure - all of it can exist in a kitchen, but it doesn’t have to be that way.

Is the stereotype of the angry chef real?

In many restaurants, yes. The military-style hierarchy in the kitchen can create a toxic environment. If you work in a 3-star Michelin restaurant and the head chef is a piece of shit, you feel you can’t complain because it can impact your career. There’s a French journalist, Nora Bouazzouni, who wrote a book called Violence in the Kitchen. She shares testimonies of many chefs and exposes the toxic culture in French kitchens and the poor conditions some workers face.

The Arbore team

How do you define success? Has this evolved over time?

Yes. My childhood dream was to own my own restaurant, open several, and still be able to spend quality time with my family. Now, success looks like the kitchen being able to run without me being there 24/7, and not cooking out of obligation.

For over 10 years, I worked overtime on weekends, sometimes 80-hour weeks. You miss so many birthdays and important moments. I want to have a family, and I don’t want to miss those things. So success now looks like freedom and quality time with family and loved ones. I’m now moving more into consulting and helping launch new projects, and I hope to eventually own my own restaurant soon.